Rescuing Scientific Posters from the Twitter Black Hole

Written by Liza Bernstein

In this piece on Symplur, Liza Bernstein, a breast cancer patient and advocate discusses three innovative endeavors around science posters. GRASP is one of them.

Thousands of research posters and abstracts are presented at medical and scientific meetings every year, but few are ever mentioned on social media — and when they are, it is with very little substance. Because of this, the healthcare community has been missing out on important opportunities to further the dissemination and impact of new research, and develop and expand professional networks.

Things, however, are starting to change for the better with posters, thanks to three innovative endeavors led by outsiders or newcomers to traditional research. We’ll take a look at the #betterposter movement, followed by the #GRASPcancer multi-stakeholder poster walkthrough. Then we’ll turn our attention to the endeavor we think has the most potential to rescue posters from the Twitter black hole: the adaptation of the #tweetorial.

“Come See Our Poster!” — A Missed Opportunity

Barriers to Tweeting About Posters

A significant, built-in barrier to effectively tweeting about research posters at healthcare conferences is the setup. Posters are tacked up on panels, presenters stand in front of them hoping for opportunities to discuss their latest research, and visitors walk by, straining to gain insights. When you stop and engage, it’s neither practical nor polite for either the presenter or the attendee to try and tweet anything but a glorified selfie in the moment.

Electronic posters, an innovative feature at many meetings including, according to Daniel Cabrera, MD, “the majority of Emergency Medicine conferences which have been electronic-poster-only for a while now” don’t make it any easier. He added, “electronic posters are difficult to tweet about as usually they are only displayed for a few minutes, and presenters are not typically allowed to share them.”

This creates a missed opportunity when it comes to using the power of social media to disseminate important research. In contrast it’s easy, and for many it’s become a note-taking reflex, to share and discuss learnings via Twitter from keynotes, panels, and other talks — just ask Deanna Attai, MD, who way back in 2012, tweeted: “it’s a good way to take notes during a meeting – just go back and re-read your tweets!”

“Come See Our Poster!”

The talk session versus poster discrepancy is reflected in the types of — limited — Twitter activity we usually see around posters. Most tweets featuring the term “poster” are a variation of the “come and see our poster” format, some amplify the work that interests them, and some include a photo of the poster. Rarely do they ever do justice to the research presented in the poster and disseminate the findings.

For example, at the 2019 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (#SABCS19), only 332 unique tweets (out of more than 20K total) included the word “poster.” This one and this one offered scheduling details, this tweet went a little further than the norm with a video promoting the researcher’s poster, and this one, from Pallawi Torka, MD amplified the work of fellow colleagues:

Disrupting the Format of the Scientific Poster: The #betterposter Movement

From NPR to Inside Higher Ed, much has already been written about Mike Morrison’s quest to radically improve the scientific research poster. And even more has been tweeted: Since March 2019, his #betterposter hashtag has racked up 20 thousand tweets, and close to 12 thousand users. (Symplur Signals subscribers who have access to the necessary datasets can view and interact with this dashboard.)

An organizational psychology PhD candidate at Michigan State University, Morrison has a background in user experience (UX) design. His frustrations with the traditional scientific poster format and what he calls the “wall of text” experience of presenting and learning from them at conferences, inspired him to rethink the old poster design. His 2019 video outlines the issues and his proposed solution; his repository provides #betterposter templates; and via his Twitter account, he invites people to experiment with the format and discuss it using the #betterposter hashtag.

Morrison’s bottom line is all about narrative, context, and the elevator summary. If scientists were to make their primary takeaways more prominent and easily grasped, it would be easier to share them rapidly.

Adoption has begun, and we’ve seen examples at meetings ranging from anesthesia to cardiology…

… with cameos from Mark Morrison himself:

Given the format’s novelty, #betterposter Twitter conversations are still focused on its relative merits. When we see greater adoption, perhaps the focus will shift to the actual research questions and conclusions.

#GRASPcancer, a Poster Program Hashtag and Experience

Meanwhile, back at #SABCS19, the inaugural GRASP (Guiding Researchers and Advocates to Scientific Partnerships) program brought new energy to the conference’s poster hall. Co-founders and patient advocates Christine Hodgdon and Julia Maués sought to bring advocates, clinicians, and researchers together for guided poster walkthroughs. As explained in this article, they recruited participants to join small teams composed of one or two novice patient advocates and a scientist or a clinician, and led by an experienced patient advocate mentor. Each team received their two poster assignments upon reporting for duty — ensuring that no stakeholder would have time to prepare in advance — and set off on their multi-directional learning tour.

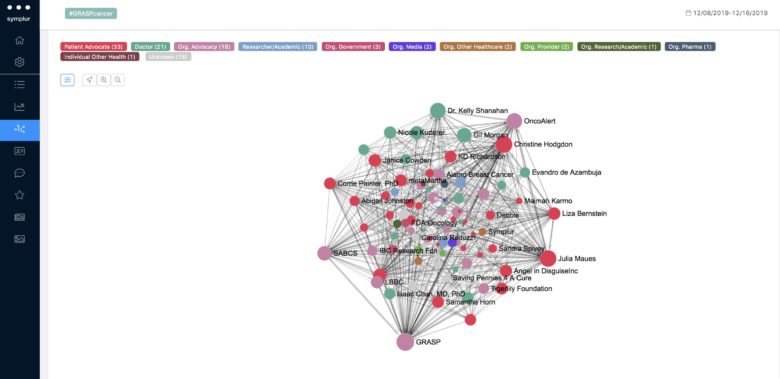

With the power of the dedicated hashtag #GRASPcancer, and Twitter networks including #BCSM and #Oncoalert, Hodgdon and Maués were able to grow what they expected to be a small pilot of 20 people to 120 participants, with many insisting on returning for the program’s second day. (Disclosure: I was an advocate mentor for GRASP, and served on both days.)

Hodgdon and Maués noted: “GRASP seeks to create a private interactive learning environment whereby: 1) patient advocates can ask questions to better understand scientific posters in a more robust and meaningful manner, and 2) members of the science community can engage directly with the people they are trying to serve, while fostering a sense of urgency and purpose to their research.”

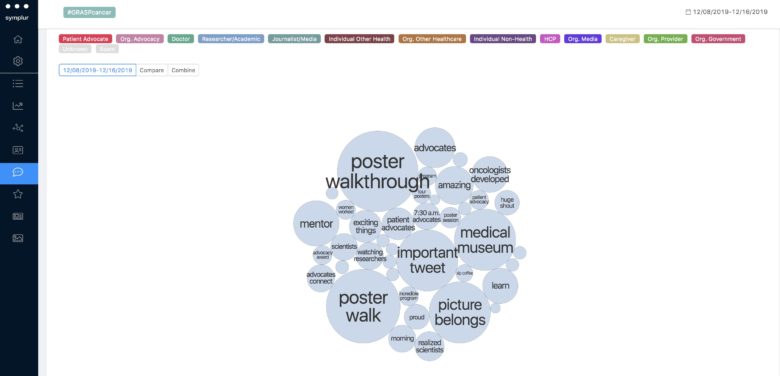

A Symplur Signals dashboard for #GRASPcancer shows intense multi-stakeholder Twitter activity around the hashtag. The initiative brought enthusiastic people together in the spirit of learning and connection, and succeeded in building community across silos. (Symplur Signals subscribers who have access to the necessary datasets can view and interact with this Dashboard.)

A study of the related transcript reveals that tweets were principally focused on the benefits, effectiveness, and fun of bidirectional learning via the structured poster walkthroughs. Inspired by GRASP, consider the innovation of creating and being disciplined about using a specific hashtag for poster-related tweets, in combination with the conference hashtag. Imagine harnessing the power of this type of community to amplify a poster’s findings to the right audiences or drive conversation about the research.

Hybridizing Tweetorials and Posters: the Liz Salmi Example

Liz Salmi, a prominent patient advocate and co-founder of the #BTSM (brain tumor social media) Twitter chat/community, presented a traditional research poster at the Society for Neuro-Oncology’s 2019 annual meeting (#SNO2019). Feeling the need to share her findings beyond the walls of the venue, she created a brief series of threaded tweets, akin to a tweetorial (an innovative and already very popular didactic tool).

“The brain tumor community on Twitter needed to know what this poster was about,” she said, and added: “it made our poster more meaningful if those who were not there in person could read the tweets and know what our findings were.”

Salmi’s Twitter thread introduced the story behind the research, shared the highlights of each of the poster’s sections (background, methods, results, etc), and credited her co-authors and her funder. She made sure to mention the individuals and organizations by their Twitter handle so that they would be notified and be able to easily retweet and amplify the thread. And, Salmi used Twitter’s photo-tagging feature to include and alert additional team members and influencers in her first tweet. She used the relevant conference and disease hashtags in her tweets, ensuring they would be seen by people following the hashtags. Finally, to pique #SNO2019 attendee curiosity, she waited until later that night, after her poster session had ended, to tweet a photo of the entire poster.

Salmi’s thoughtful use of Twitter’s features provided built-in ways to disseminate and amplify her team’s work. Her seven threaded tweets created both an easily digestible narrative and a highly effective digital footprint for their research. Her proficiency with healthcare Twitter, her background as a communications professional, and her personal challenge to submit a poster to a world-class medical conference as a non-traditional researcher are some of the factors that led Salmi to create her tweetorial.

As an aside, Salmi revealed she used Morrison’s #betterposter design in some of her early poster drafts, but concluded that given her outsider status as a patient advocate, it would be wise to use the expected format. She did add one of his recommended features to her poster: a QR code linking to her raw data, which was none other than a Symplur tweetchat transcript.

In conclusion, Salmi said: “The potential for Twitter as a strategy for research dissemination is exponential. Conference posters are usually a single use experience, and that’s a waste. Transforming your poster into a tweetorial ensures it lives on beyond the conference, and reaches people who were unable to attend the in-person event.”

Tips For Communicating About Posters and Abstracts on Twitter

The three initiatives highlighted in this post are catalyzing the research community to develop better ways to share and democratize the science presented in posters and abstracts. With a little effort, creativity, and strategy, we can accelerate the possibilities for connection, collaboration, and scientific progress by taking posters and abstracts out of the social media black hole. To that end, consider the following:

- Need To Know: Regardless of the design format, create a poster that focuses on what you need your audiences to know.

- Consider Your Audiences: beyond your immediate colleagues, say clinicians or computational biologists, who else might need to know about your findings right now? Consider the reach of patient advocates, journalists, and other stakeholders in your area. Who else can help to disseminate and amplify your work quickly?

- Sum it Up in One Tweet: To take what Morrison advises further, write your conclusions in plain English, and in doing so, limit yourself to 280 characters.

- Twitter 101: Include your twitter handle on your poster. Add those of your co-authors as well as any other relevant accounts such as your organization, your funders, etc.

- Tweetorial Must Dos: Combine all the above with a thoughtfully crafted tweetorial that gives context to your research (narrative), provides overviews of each of your poster’s sections, pings the appropriate Twitter accounts (colleagues, co-authors, funders, influencers) and hashtags (the conference, your field, your communities, etc.), and links to a webpage that contains additional information.

- Practice Hashtag Discipline: Use the conference hashtag in each of your tweetorial’s tweets. It’s ok to only include any disease or community hashtags in its first tweet. And, make sure to include #tweetorial in its first tweet!

- For Conference Organizers: Add social media dissemination recommendations and requirements to your calls for posters and abstracts. Consider creating a poster-specific hashtag for use in conjunction with your conference’s hashtag. Publicize the hashtags widely.

- Interact, interact, interact! Do your part to build community and engage in dialogue about your poster on Twitter (remember to use the appropriate hashtags in each of your tweets and replies!). It will expand your network, impact the science, and help your career!